This is the third entry on using Sam Barlow’s Her Story video game to study unreliable narrators in my 9th grade English class. The first entry can be read here and the second here. This will focus on how we played Her Story in class, the final writing assessments, and student feedback along with my own reflections.

Is This a Game to You?

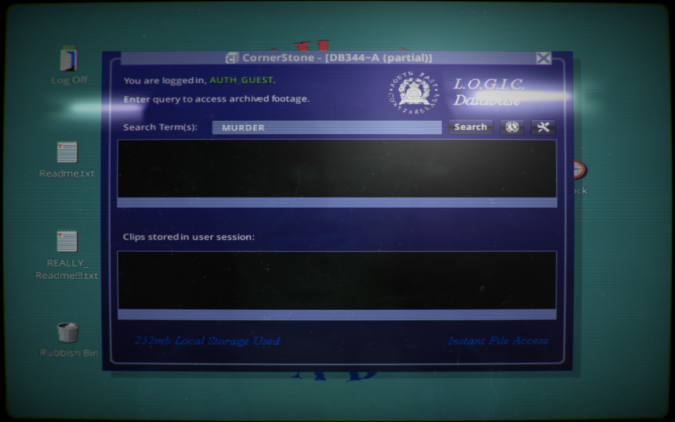

I hinted and teased my 9th graders that this unit would be a little different. I’ve used video games as texts in my class for a few years, so they knew some type of video game was coming. We had spent several days breaking down the unreliable narrator: their methods of lying, dissembling, (mis/dis)informing, and how a reader can construct an understanding from that unreliable narrative. After finishing our discussion of In a Grove – and its modernist skepticism of objective truth – I turned on the projector which displayed the virtual desktop of the “L.O.G.I.C. database”, the central interface of the game:

Note the virtual reflections on the antique CRT “screen” the game emulates. Sam Barlow did a fantastic job making the game’s interface itself immerse you in the narrative.

I purposely did not show the title screen, or give away the title of the game (despite their insistent demands). I wanted to give a sense of mystery but also deter students from instantly Googling the game and gorging on spoilers.

The first instruction was to open a clean copy of the Narrator Table on their laptop. As Matthew Farber noted in his excellent new book Game Based Learning in Action, game based learning organically lends itself to Montessori style instruction:

A Montessori-like approach was also observed in how games were contextualized to students. “Brevity” is how Montessori (1912/2012, p. 61) described how long an explanation should take before students engage in a learning activity. (Farber 121)

Without realizing it, I embraced a very Montessorian style of introduction for Her Story. I explained to them that we had studied unreliable narrators, examined their methods, built up “defenses” against them, but the time for theory was over. It was time for them to prove they could grapple with an unreliable narrator.

I gave them a quick narrative overview: you are sitting at computer in a police department archive. You have access to a series of clips that have been fragmented and disorganized, but you can search the clips through the words spoken by the subject. At this point, I hit Enter and the pre-filled search term of MURDER is executed (the game starts that way). Five clips – which I explain is the limit for any single search term – appear and I explain how they can be viewed, annotated, and bookmarked for later study. Then I cede the laptop (connected to the projector) to a volunteer student. They can rotate who “drives” on their own. At this point, I’m pretty much done and I step away to observe.

It’s time for their final exam.

Hello, Hannah

As they dug into the text, I encouraged them to keep the debate lively. They obviously need to (and did) listen closely as each clip was played, but between clips crosstalk, debate, and “backseat driving” was the norm. This is informally known as the “hot seat” method of game based instruction. As a 1:1 laptop school, I could have given each of my students a copy and had them play on their own. In fact, this was the model I used when teaching Gone Home as a text (see Paul Darvasi’s excellent blog for more about studying that game as a text in English class), but I sensed that this wouldn’t be ideal for Her Story‘s complex narrative that has players grappling with constantly shifting interpretations and a non-linear plot. This is a story that would need to be experienced with the safety of numbers.

Fortunately, my instincts paid off. The students reported in post-unit feedback that the social format of playing the game not only aided comprehension but was more fun as well. For example, one student said:

The class as a whole was also a lot more vibrant when playing [the game]

And:

My peers and I were able to be more enthusiastic with Her Story because we played it together and some of my fondest memories of school were when we did find out new info on the case and the whole class freaked out

This type of experience and engagement is backed up in the research as well. A meta-analysis by the Journal of Educational Psychology found that collaborative play was significantly more effective in learning outcomes compared to solitary play, by two standard deviations or more. (By the way, the research in general on game based learning is quite bullish.)

This is encouraging for several reasons. One, this lowers the financial barrier for teachers interested in using commercial games in the classroom. You don’t need 30 copies of Her Story to effectively teach it. I should note, however, that small publishers are often amenable to helping teachers acquire copies of their games. In the experience of many GBL teachers, if you contact an indie developer and explain you are seeking copies for the classroom, it is not uncommon to be offered discounts or even provided free copies. But again, the hot seat method can defray the cost, too, and in some cases may even be preferable to a 1:1 model. I would imagine a class of 30 might get too crowded, but two or three groups of 10-15 is far more manageable.

This model allowed students to take detailed notes using their Narrator Table. The student in the hot seat was given notes from the day by a classmate of their choice. In fact, one student who often had difficulty with reading and writing was the most diligent, detailed note taker. He ended up filling pages and pages of thorough notes, often making insightful connections and interpretations on the fly. This Table was collected and graded along with their final writing assessment.

The Write Way to Play

As the students began to play, they quickly brought their analytical skills to bear. Theories were developed, modified, eliminated, and resurrected as the plot thickened. Competing theories began to emerge as well, but it did not derail their exploration. After about five days (three hours of class time), we wrapped up our play time. Two to three hours is likely sufficient to have a firm grasp of the narrative but – perhaps a minor spoiler! – there is a major interpretative choice to make that is never objectively resolved. Students will likely know what side they fall on, or become comfortable with the ambiguity, after that much time. Unlocking every single clip is not necessary to feel like the story is “complete”. To prepare them for their writing assessments, I provided them with two supplemental resources that “unlock” the entire game to speed up their acquisition of necessary elements.

(Massive spoilers behind the next two links!)

First is a YouTube fan video that compiles all of the clips into chronological order.

Second, and which my students found the most useful, is a transcript of all the clips, also in chronological order.

Armed with these (and copies of the game), they broke into two affinity groups based on what type of assignment they found the most interesting. Here were the two options:

This is an overview of the two writing options from a presentation I gave at the Games in Education symposium last summer

This is an overview of the two writing options from a presentation I gave at the Games in Education symposium last summer

The students were given exemplar texts to study and discuss, in addition to some reflection questions they had to answer in our online discussion forum (used all year for homework responses). I used a Vanity Fair cold-case article that was recommended to me by a colleague with a journalism background. This article was perfect because recordings of police interviews played a major part in the narrative, just like Her Story would for their version. They had to take on the part of an investigative journalist who has discovered the clips (in reality, discerning the identity of the “viewer” is a late plot element in the game) and is trying to piece together what really happened. This option was geared towards those who have the urge to untangle and explain complicated narrative knots.

The second group analyzed and discussed professional video game reviews. I didn’t want them copying or being influenced by existing reviews of Her Story, so I emailed the editors of my favorite review outlet, Polygon, and asked if they had a style guide or other guiding material for structuring their reviews. They did not have anything formal, but Arthur Gies, the Reviews Editor at the time, did have some delightful things to say about their review writing process, at least for an English teacher:

Our basic structure is the 5-part argumentative thesis-based essay, with an avoidance of passive voice and assuming responsibility for one’s own thoughts and opinions.

Wonderful. And who said five paragraph essays are useless?

Also:

Not every site uses [the thesis based essay model], and sometimes we don’t, but I also feel like our reviews go for clarity of thought and opinion above all. We’re not a commercial – our reviews exist to tell you what a person thought of a game, holistically. The thesis backed structure is great for that, and is a sound basis for just about any argumentative/advocative piece.

Couldn’t have said it better myself.

However, Arthur was even more helpful by providing me with three exemplar reviews that he considered to be good models. The students going down the review track had to read those three reviews and answer reflection questions to further understand the format. Then, following that model, they had to write their own professional style review of Her Story. This option appealed to students who are interested in the medium of video games and how it is both expanding and changing, as well as those that are comfortable and/or enjoy writing persuasively.

I was impressed by the depth of the reviews and articles. The articles were dramatic and compelling in their reconstruction of the narrative. One student who wrote a cold case said he essentially wrote two different versions of the article because he was constantly “at war” (his words) with himself over which interpretation he believed. He bathed in the struggle. I couldn’t have been prouder!

Several reviews made mature observations about not only the narrative but the format as well. They understood how and why the unreliability affected and drove the story, and also why it was disorganized and fragmented. They made connections about a new medium without my input. This was true Montessori style learning – I let them explore, I let them make the leaps. I just watched.

Won’t Someone Think of the Children?

So, what did the students think? The response was overwhelmingly positive – perhaps not unexpected – but so was the effort and engagement. From beginning to end, the students were focused, enthusiastic, and diligent.

However, I am always quick to point out that we shouldn’t assume all our students (especially boys) are “gamers” who will be intellectually and emotionally electrified by the mere presence of a video game in class. In fact, a good number of students I’ve taught are skeptical at first, but once they see that this exercise isn’t frivolous they are enthusiastic. But game based learning teachers should be careful not to fall into the “digital native” fallacy and assume because they are using new and interactive media that their students will be automatically enthralled, or even comfortable. Elements like the hot seat model can help those who are less comfortable with the medium and I advocate for always giving students as much agency and choice as possible. That said, I have never had a student throw their hands up and reject a game based learning unit. But, I have had some who are candid in letting me know it is not their preferred method of learning. You should teach (or not teach) the games that best reflect you, your students, and your community. Fortunately, there are countless options out there. Her Story is only one of many.

One thing I want to repeat is they were also having fun before, during, and after playing the game. I am a big believer in the maxim popular with those who take their play seriously: “The opposite of play isn’t work; it’s depression.”

With that in mind, this comment from a student particularly struck me:

…the unit [felt] more like an investigative game than a test and this meant that the dread and stress that were apart [sic] of normal exams were replaced by excitement and joy.

“Dread” and “Stress” vs. “Excitement” and “Joy”.

I know which I’ll take every time.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.